WHEN JERMELL COLEMAN was a high schooler in Detroit, he occasionally helped the local “tree man” cut limbs and branches, but he never expected to pursue a career in urban forestry. Yet decades later he’s now employed by the new Detroit Tree Equity Partnership (DTEP), working to increase the equitable distribution of trees around the city — a concept called Tree Equity.

Photo Credit: Cokko Swain / American Forests

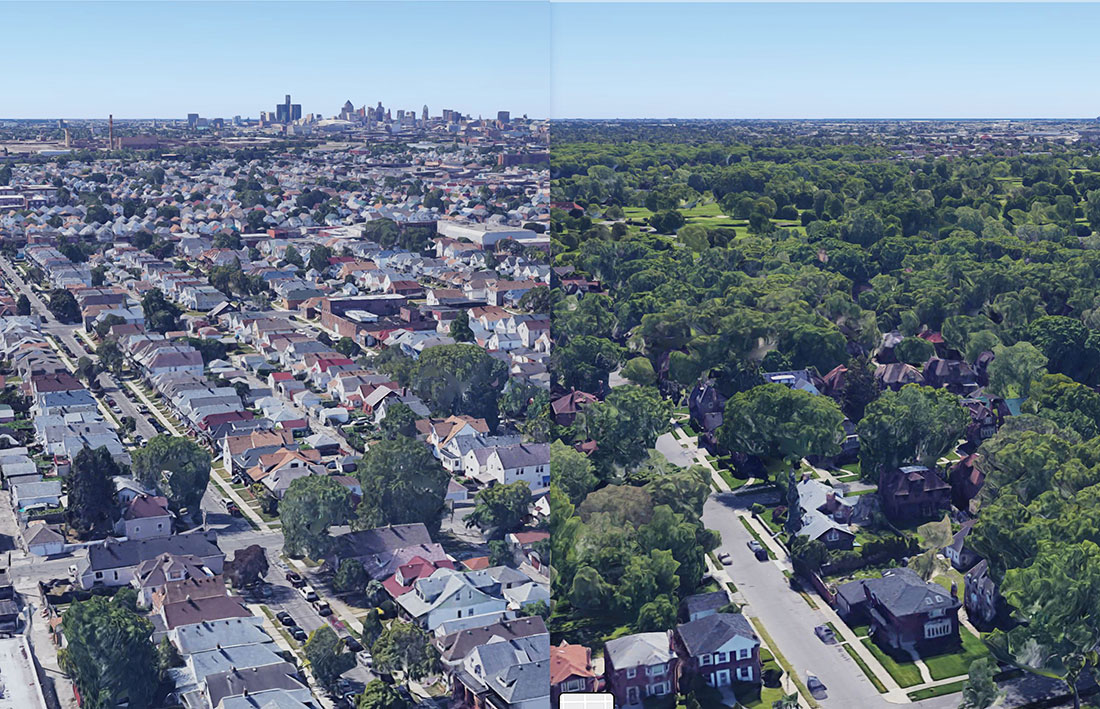

Tree Equity work is needed because communities of color have 45% less tree canopy on average than predominantly white neighborhoods, and low-income areas have 36% less tree canopy on average than the wealthiest neighborhoods. This is a problem because trees provide important benefits, such as heat reduction that can save lives, improved air quality and recreational access.

The partnership, a major civic initiative launched publicly by DTE Energy, American Forests, the City of Detroit, The Greening of Detroit and an array of additional partners in October 2022, has ambitious goals for its first five-years: planting 75,000 trees, investing $30 million in greening Detroit neighborhoods and placing more than 300 Detroit residents in jobs in the tree-care industry.

“We have a lot of big goals for DTEP,” says Jenni Shockling, American Forests’ senior manager of urban forestry in Detroit. “But it all starts with ‘the one.’ The one tree we plant or maintain that survives to realize its full potential; the one resident who has opportunity and takes pride in what they do; the one case of asthma or heat illness that may be prevented.”

Coleman, now 42, is one of those residents finding new opportunity with the project. After his release from a six-year stint in federal prison in early 2022, he participated in The Greening of Detroit’s training program, Detroit Conservation Corps (DCC). After graduating from the DCC program and learning how to be a “tree man” in his own right, he joined the 10-man DTEP Flex Crew, which plants an average of 45 trees each day in season.

It’s a job that provides its own satisfactions, as well as inspiring the joy of community members who appreciate the improvement in the city they love.

“There’s a feeling of accomplishment, of pride,” he says. “And I haven’t seen this many smiles from strangers since I’ve been home [from prison]. There are a lot who are very happy about it; I’d go so far as to say ‘elated.’ People pull over when they see us and just clap.”

Photo Credit: Cyrus Tetteh / City of Detroit

DIVING DEEP IN DETROIT

Creating robust, effective urban forestry requires much more than putting trees in the ground. It starts with building partnerships, which are the bedrock of DTEP. A slew of public- and private-sector stakeholders have been involved since the first planning stages in 2016. Groups of participants meet as often as once a week to hash out everything from big-picture concepts to detailed logistics. DTE Energy is a driving force behind this work, helping position the effort with elected officials and other corporate and philanthropic funders in the city.

The partnership seeks to embody servant leadership and elevate community perspectives. DTEP does this by working to include city residents in meaningful ways, as decision makers, neighborhood experts and long-term stewards.

The goal is to develop a model that progresses from year to year, and that can adapt as a city’s urban forestry priorities evolve.

“When we think about the long-term climate issues we’re seeing — from flooding to extreme heat — those most impacted should have a say in the solutions. All of these steps and the processes that we’re thinking of putting in place are about that.” — Alexis Gomez, senior manager of community engagement at American Forests

Science guides every step of this partner-ship’s work. It begins with the Tree Equity Score (TES), a first-of-its-kind, free, public tool that synthesizes complex data into a single number for every neighborhood to focus limited resources on maximum impact. To turn that number into action, the partnership deploys American Forests’ comprehensive “change model” that incorporates a suite of technical tools, analyses and initiatives to help optimize urban forests for climate and public health benefits and achieve Tree Equity. These include community engagement, workforce development expertise and innovative financing. The change model also incorporates tree nurseries of genetically resistant varieties in vacant lots and building a local Tree Equity Score Analyzer tool, which allows local users to do scenario planning down to the parcel level.

As the first city to incorporate every aspect of this change model, Detroit offers lessons for other cities that are looking to increase Tree Equity.

“I really like how this is unfolding, and how this model we’re creating could be picked up and taken to other areas outside of Detroit,” says Christy Clark, director of the environmental management and safety group at DTE and the company’s coordinator for DTEP. “It’s fantastic.”

Photo Credit: Google Maps / American Forests

“A VIRTUOUS CIRCLE”

The partnership is also making the city’s tree-care job training and employment pipeline more efficient by coordinating two existing programs that aim to help people get long-term, secure employment in the industry. These are DTE’s Tree Trim Academy, which helps Detroiters pursue careers as tree trimmers, and Detroit Conservation Corps, a workforce training program in urban forestry run by The Greening of Detroit.

“That tree that we’re putting in the ground is providing a job, which provides a wage, which is providing a livable income for an individual to live and succeed in life. It isn’t just changing the landscape, but it’s truly changing the lives of individuals.” — Monica Tabares, vice president of operations and development at The Greening of Detroit

And beyond those benefits, it’s influencing the city’s economy, says Eric Candela, director of local government relations for American Forests: “We have the trees being grown in Detroit and planted in Detroit neighborhoods by Detroit residents. It’s kind of a virtuous circle that keeps all the funding and opportunity in Detroit.”

Coleman is a poster child for this approach. The neighborhood of his youth was full of trees — “It was shady and comfortable,” he remembers. But over time, pests, diseases and weather wiped out the leafy canopy. “There used to be a tree at every house, and now you’re lucky if you get a tree per block.”

Living there again, he is now planting with his crew in nearby areas and feeling satisfaction from supporting his family by bringing nature back to struggling neighborhoods like his.

“This is my city,” he says. “I get this real feeling of ‘I’m at home.’ It feels like it’s getting to be Detroit again.”

Photo Credit: Cokko Swain / American Forests

CREATING A BETTER COMMUNITY

At the center of DTEP’s approach is treating trees as assets that can support job and business opportunities, keep money in the community, and provide benefits for neighborhood safety, public health and recreational access.

“We’re leading with equity, we’ve expanded capacity and we’re looking at innovative funding mechanisms,” Candela says. “The net effect is that people who live and work here are going to experience a much-improved quality of life… It’s holistic and it’s sustainable.”

For residents like Erica Mixon, 49, the return of trees couldn’t be more important for quality of life. Growing up in Detroit’s leafy Rosedale Park area, she often sought solace for tumultuous emotions under a tree.

“All I knew how to do was pretend that things were all right, but in nature things were all right,” she remembers. “Those were moments when things were okay, and I felt safe.”

When she moved to her grandfather’s house in a part of the city devoid of trees, she experienced what she calls a profound “culture shock.” The leafless neighborhood — the site of a civil rights uprising in 1967 and a casualty of the subsequent crack epidemic — felt hot and desolate.

Now, more than three decades later, Mixon is a professional booster for the residents of that same community in her role as a community advocate for Central Detroit Christian Community Development Corporation. One thing she does in that role is help residents see the power of nature to improve their quality of life.

Photo Credit: Joel Clark / American Forests

“I would so often say to myself ‘I can’t wait to be an adult so I can move far away from here,’” she says. “And now I’m that area’s community advocate, and I am proud to be that.”

She calls this irony, but it’s also a sign of the power of civic engagement. By building on such pride-of-place and desire for change, DTEP is building a groundswell of support for trees and the benefits they bring — not a given in many Detroit neighborhoods.

“A lot of citizens believe the trees might be a problem for the plumbing; I’ve heard several reasons they might not want a tree near their residence,” says Coleman. But “as soon as it’s explained to them, they want more than one tree. They want to place trees all around the house.”

The work is as much resident-to-resident as it is directed by the many organizational partners that unite to push it forward. Coleman often speaks to people whose neighborhoods the team is planting in, his chattiness making him the crew’s unofficial spokesman. “It’s a great feeling to spread the understanding as well as participate in putting [trees] there,” he says. “There are a lot of positive feelings tied with this job. There is a great benefit to me mentally to be coming into such a positive work environment and doing such a positive thing… You see smiles from people who are happy to see their city improving, tree by tree.”

Katherine Gustafson is a freelance writer specializing in helping mission-driven changemakers like tech disruptors and dynamic nonprofits tell their stories.