By Dylan Stuntz, American Forests

The grey cover of “And Again: Photographs from the Harvard Forest” is adorned with a simple ink drawing of a small pine branch with cones, but much like the subject of the book, there is a hidden treasure found inside. There is both beauty and science found within the woods of the Harvard Forest, and John Hirsch works to uncover both, while demonstrating how each feeds into the other.

“And Again” is a deceptively complex volume, both in terms of the photos and essays inside, as well as the composition and design choices. The essays, written by David Foster, Clarisse Hart and Margot Anne Kelley, offer contextual background on the forest’s history and work.

The subject of the book is the Harvard Forest, a 3,750-acre plot of woodland used for scientific experimentation, research and study found in Petersham, Mass.“It is a place where technology and nature are so viscerally and overtly entwined that cables and wires emerge from the ground and descend from the sky. Trees are wrapped in plastic and metal, and the growth and movement of all things are tracked with unending precision.”As other essays explain, the Harvard Forest is made up of so much more than simply the trees inside it. It is a place that has been cared for and observed for decades, making it a metaphor for most modern forests, as humanity traipses through and leaves impacts both intended and unintended.

The boldest design choice throughout the story is the deliberate decision to leave almost a third of the pages blank. Opening the book to a random spread will most likely result in a photograph on the right-hand page, with the leftmost page remaining empty. However, this vacancy serves to emphasize pages that do feature a double spread, whether they be essays paired with photos or two photos placed together.

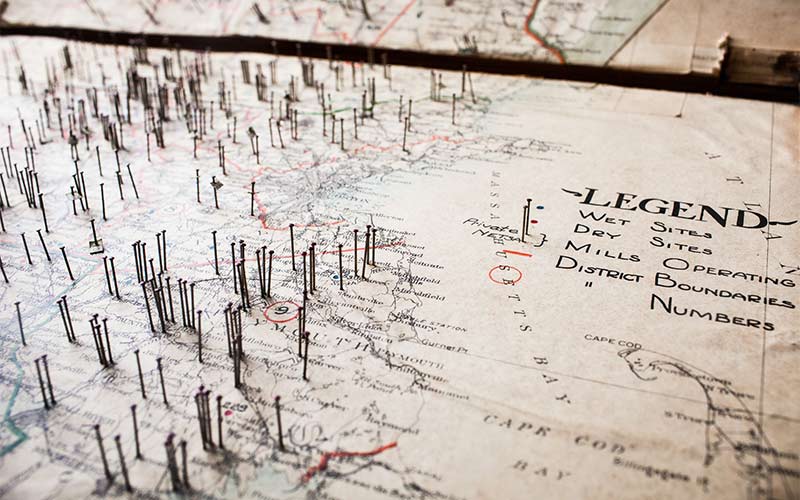

The pairings initially seem random, however, after a moment, a larger design starts to emerge. Two photos placed side-by-side on pages 88 and 89 are titled “Relief Map of Petersham and the Harvard Forest” and “Air Sampling Tubes and Electrical Wires.” Both feature strong man-made lines in different contexts, with a relief map featuring the changes in elevation in one picture, while wires hang from trees and run through the air in the other. It creates a sense of artistic continuity between the pages, connecting two photos that seem to simply share a photographer and a location, expanding into so much more. The word “story” legitimately applies to this book of photos, because a sense of connection grows stronger the deeper one gets into the volume.

Almost every photo featured shows humanity’s relationship with this piece of woodland, whether it be the shadow of a fire tower or punch cards from the archives. Some tell a more subtle story of the people, juxtaposing a tree stand titled “Clear-Cut” with a second stand, simply titled “Shelterwood.” People are featured in some photos, but they are never focused on the camera, either lost in a specific task or deep in thought, caught in a perfectly candid moment, as much a part of the environment as the trees they study. One photo, titled “Julian in the Hemlock Tower Shed,” features a figure (presumably Julian) standing in a moment of clarity, eyes closed and hand placed over his chest. It is a uniquely intimate moment that demonstrates the exceptional relationship between the forest and its stewards.

The volume opens with a quote by Hugh M. Raup, who studied the previous owners of the land, farmers who cared for it from 1763 to 1845: “And again the land did not change, except in terms of the human values at the time.” Hirsch’s story shows that certain people are trying to maintain a reverence for this forest that remains as unchanging as the land.